Java String pool Example

In this example we are going to talk about a very interesting subject, Java String pool.

As the name suggest, String pool is a pool, or else a set, of String objects located in a special place in Java Heap. Java creators introduced this String pool construct as an optimization on the way String objects are allocated and stored.

String is one of the most used types in Java, and it is a costly one when it comes to memory space. For example, a 4 character long String requires 56 bytes of memory.

Which shows that only 14% percent of the allocated memory is the actual data, the 4 characters. So, a lot of overhead there. Naturally, an optimization should be implemented on how String objects are going to be stored in the heap. This is why the String pool was created. It is a simple implementation of the Flyweight pattern, which in essence, says this : when a lot of data is common among several objects, it is better to just share the same instance of that data than creating several different “copies” of it. Applying that to Strings, its better to share the same String object than creating multiple instances of String objects with the same value.

1. String pool examples

Let’s take a look at this snippet :

package com.javacodegeeks.core.lang.string;

public class StringConcatenationExample {

public static void main(String[]args){

String str1 = "abc";

String str2 = "abc";

System.out.println(str1 == str2);

System.out.println(str1 == "abc");

}

}This will output:

true

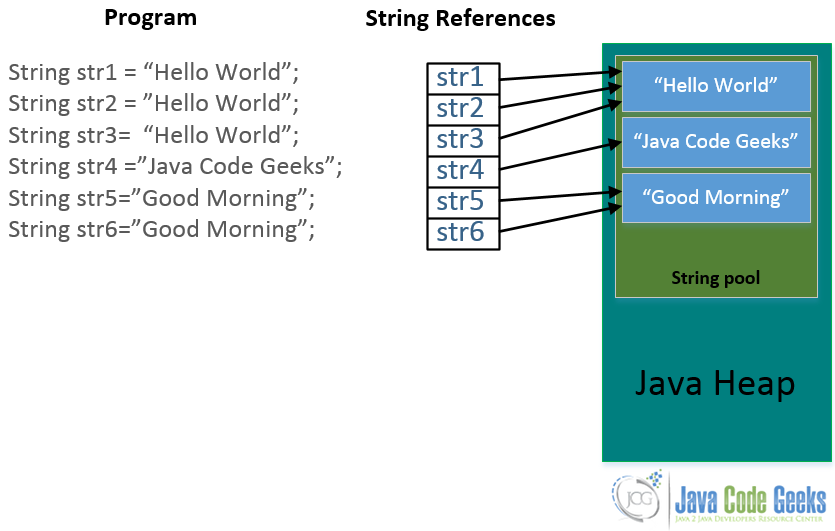

trueSo as you can see str1 and str1 are pointing to the same String object. Here is a picture that shows how the string pool is actually maintained in the heap:

Strings with the same value are actually referring to the same String instance. In that pool, a String object with value “Hello World” is only created and stored once. Any other String that gets the value “Hello World” (statically – hard coded, using literals) will reference the same String object in the pool. So, every time you create a String using a literal, the system will search that pool and check if the value of the literal exists in a String object of the pool. If it does, it returns back the reference to that matching object, and if not, it creates a new String object and stores it in the pool. The aforementioned comparison is of course case sensitive and its actually implemented using String#equals. So, String references, initialized with the same literals, will point to the same String object.

Now, you can also see a reason why Strings are immutable. Imagine thread A creating a local string “Hello World” and then a second thread B creating his own local string “Hello World”. These two threads will share the same String object. Supposing String was mutable, if thread A changed the String, the change would affect thread B, but in a meaningless (some times catastrophic) way.

Now take a look at this :

package com.javacodegeeks.core.lang.string;

public class StringConcatenationExample {

public static void main(String[]args){

String str1 = "abc";

String str2 = "abc";

String str3 = new String("abc");

System.out.println(str1 == str2);

System.out.println(str1 == str3);

}

}This will output:

true

falseThis means that str3 is not pointing to the same String object in the pool. That’s because when using new to create a new String, you implicitly create a brand new object in the heap every time, like you would with any other object in fact. So this String instance is not stored in the String pool, but in the “normal” heap segment.

Here is another example with the same behavior:

package com.javacodegeeks.core.lang.string;

public class StringConcatenationExample {

public static void main(String[]args){

String str1 = "abc";

String str2 = "ab";

str2 = str2+"c";

System.out.println("str1 :" +str1+", str2 :"+str2);

System.out.println(str1 == str2);

}

}This will output:

str1 :abc, str2 :abc

falseBecause Strings are immutable, when using + operator to concatenate two strings, a brand new String is created. The underlying code is actually using a StringBuffer to implement the concatenation, but the point is that the new String is allocated “normally” in the heap and not in the string pool.

And yet another common case with the same behavior :

package com.javacodegeeks.core.lang.string;

import java.io.BufferedReader;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.io.InputStreamReader;

public class StringConcatenationExample {

public static void main(String[]args) throws IOException{

String str1 = "abc";

BufferedReader bufferRead = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(System.in));

System.out.print("Type in a sting :");

String str2 = bufferRead.readLine();

System.out.println("str1 :" +str1+", str2 :"+str2);

System.out.println(str1 == str2);

}

}This will output:

Type in a sting :abc

str1 :abc, str2 :abc

false

The conclusion of the above snippets is that, only when initializing a String using a string literal, the String pooling mechanisms comes into place.

2. String interning

As we’ve seen the pool mechanism is not always used. But what can you do, to save up valuable space when creating a big application, that requires the creation of vast numbers of strings. For example, imagine that you create an application that has to hold addresses for users living in Greece. Let’s say that you are using a structure like this to hold the addresses:

class Address{

private String city;

private String street;

private String streetNumber;

private String zipCode;

}There are four million people living in Athens, so consider the massive waste of space should you store four million String objects with value “Athens” in the city field. In order to pool those non hard coded Strings, there is an API method called intern, and can be used like so:

String s1 = "abc";

String s2= "abc";

String s3 = new String("abc");

System.out.println(s1 == s2);

System.out.println(s1 == s3);

s3 = s3.intern();

System.out.println(s1==s3);This will output:

true

false

trueWhen calling intern, the system follows the same procedure as if we did s3 = “abc”, but without using literals.

But be careful. Before Java 7, this pool was located in a special place in the Java Heap, called PermGen. PermGen is of fixed size, and can only hold a limited amount of string literals. So, interning should be used with ease. From Java 7 onwards, the pool will be stored in the normal heap, like any other object (making them eligible for garbage collection), in a form of a hashmap and you can adjust its size using -XX:StringTableSize option. Having said that, you could potentially create your own String pool for that matter, but don’t bother.

Download the source code

This was an example on Java String pool. You can download the source code of this example here : StringPoolExample,zip

Good content. Keep up the good work.